Midway: Chapter 24

“Come along now Bao, don’t dawdle…”

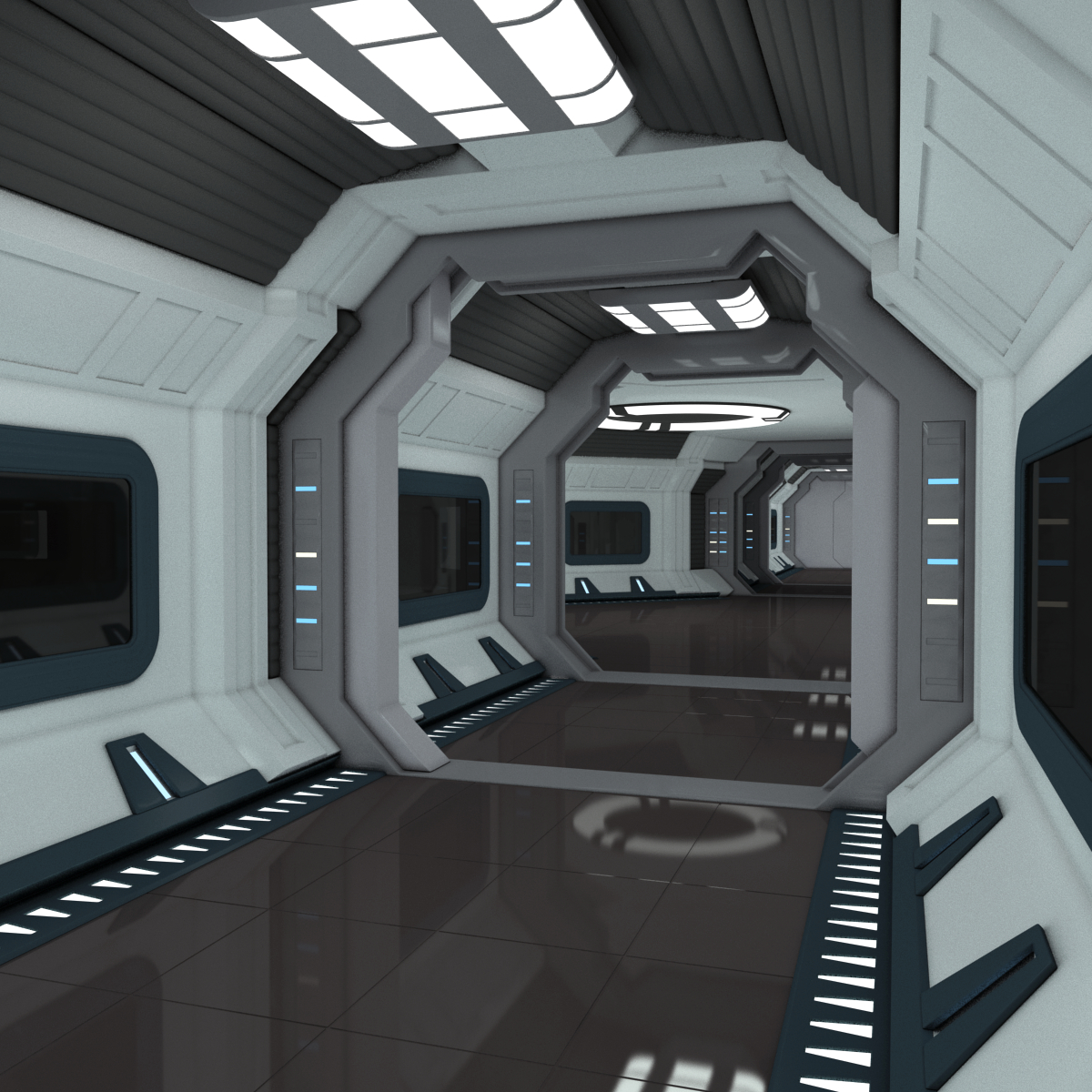

“Yes Amma.” The girl picked up speed to catch up with her mother and father as they walked down the hall together.

“Aren’t you excited? We’re on our way to order you a brother!” At that Bao beamed, and grabbed the left hand of her mother and the right hand of her father and walked between them, trying to get them to swing her. She was too old for that and they resisted at first, but they soon succumbed and swung her back and forth through the air between them.

To say that they were on their way to order a brother was a perfectly appropriate way to describe it, but Sun Jung had nevertheless said it to her daughter a bit in jest. There was no natural breeding on the ship at all, nor had there been any since the ship initially launched. In such a limited population, and over such a long time, it was essential to carefully monitor and orchestrate what genetic blending was allowed to occur. While it might have had a certain poetic grace to allow everyone to breed at their leisure and discretion, a variety of issues made this impractical at best, and dangerous at worst.

For one, unrestricted breeding could lead to a rapid overpopulation of the ship. It was exceedingly rare for anyone to die on the ship of anything other than extreme old age, so continually creating more children than replacement would quickly lead to the ship being overrun and to the depletion of their carefully managed resources. So, a very specific population growth and maintenance protocol had been conceived and instituted on the ship.

The original members of the crew who left earth numbered exactly one hundred, and were all between thirty and sixty years old. They were all expected to have children within the first ten years, which initially doubled the crew to two hundred; this constituted the second generation cohort on the ship who were today between seventy and eighty years old. When they themselves were between thirty and fifty, they too were expected to have children, resulting in the third generation who were themselves between thirty and fifty today. This brought the ship’s population up to its proscribed three hundred.

Currently new children were only born to numerically replace the people who died. Bao’s family had been next in line when the murder had occurred so now finally they were able to procure a brother for her. A new problem had also finally become impossible to ignore as a result of the murder. He had never had a child of his own to replace himself, so now there was actually a deficit of two on the ship. It also meant that they had never actually made it to the full three hundred, and now an official policy would have to be instituted regarding what to do about those who were really not going to have children of their own.

It was not just the man who died either, but those who were still young enough and were increasingly making it perfectly clear that they had no intention of having any children at all. Until they were actually faced with the reality of somebody dying after never having replaced themselves, most people ignored the problem and hoped it would just go away. Now they would need to create and establish new and specific protocols around how to go about allotting third children to those who were willing to carry the extra burden. They would also have to figure out how to conjoin multiple living suites into larger ones to accommodate the larger families, but this would probably turn out to be the easier part.

The technology existed to grow new fetus’ in an artificial womb, effectively a vat of artificial amniotic fluid and an apparatus to mimic the function on the mother’s side of the umbilical cord. It was still preferred however, for mothers to carry pregnancies naturally, even if the fetus’ conception was anything but natural. Besides not having anywhere near the resources to artificially incubate every birth along the way, the reality was that the option would be unlikely to be available in the long term once they arrived on Haven, and nobody wanted any kind of aversion to a natural pregnancy to develop. To date, the equipment had only ever been used to incubate the occasional pet or experimental animals like Tycho’s glow in the dark guinea pigs, which were originally conceived as the latter, but were now the former.

Beyond these concerns though, there was ample evidence that a natural pregnancy and birth had certain physiological and psychological bonding mechanisms between mother and child built into them. The wisdom of the day was that wherever possible such natural bonding mechanism should be preserved. It was also the case that artificial breast milk could be provided from a particular variant of the schmilk producing glands. It too was avoided based on the same appreciation of the natural bonding mechanisms between mother and baby, but it was also always substantially better than anything which could be replicated. Synergistic biochemistry between the mother and the baby was continually adjusting the temperature and constituency of the milk and in this case, scientists had yet to figure out how to best nature.

Long ago, well before the launch of the New Horizon, the reproductive elements of sexuality on Earth had been divorced from its recreational elements. Accidental or unplanned pregnancies had become exceptionally rare and occurred only with the supremely negligent and careless. There was after all a wide variety of contraceptive measures readily availability to both sexes. When all pregnancies became planned and deliberate, sex became the exclusive domain of hedonic pleasure. While many still played the sexual conquest game with each other, for many others sex became exclusively the domain of deepening bonds between lovers, or a resonant expression of affection between sexually compatible friends.

Reproduction was handled very differently now and onboard the ship than in ancient times; it was handled very carefully here. Until children were born who would be of breeding age upon arrival, vasectomies were performed on all male babies soon after birth, and once the arrival generation began being born, women of reproductive age were instead implanted with a less permanent intrauterine device. Each pregnancy on the ship was carefully planned, and the genetic profile of each child carefully considered. One of the primary reasons for this diligence was for the proper preservation and genetic segregation of the six primary ethnicities onboard.

The primary ethnicities were broad ethnic categories within which much of the original variation was lost, but between the six ethnicities a great deal of genetic differentiation was preserved. At the time of the launch it was hard enough to recruit people who could qualify as ethnically ‘pure-bred’ anything, and it was essential to maintain those divisions on the ship. A lot of genetic variability was sadly and unavoidably lost by lumping together only six predominant ethnicities, but so much more would have been lost if no such efforts had been made at all.

There was no preferential racism involved in the ancient understanding of the word; instead this genetic segregation was a biological imperative as opposed to a social one. On the ship this differentiation between the groups was celebrated, as part of what gave the mission a good chance for success and never had there been thoughts of any of these groups being superior to the others. They were all humans, and the only group that mattered to anyone on the ship was the rest of the crew who were all regarded as extended family.

It was well understood that whatever differences might be claimed to exist between these segregated groups, there was far more variation between any two individuals on the ship than between any two ethnicities at large. Genes after all, a person does not make. They were all humans first, and any visible differences between them were just that. Their personal differences where they existed, were far more relevant to them than anything to do with any ethnic or cultural differences.

Human success as a species was from the very beginning based largely in its behavioural variability. It could be argued that humanity’s central and most successful evolutionary adaptation is adaptability itself; the ability to use powerful brains, articulate hands, and sophisticated teamwork to discover a way to survive in almost any environment on Earth. That is why humans populated almost every place on Earth in so short a time after their initial migrations out of Africa.

Preservation of the great ethnicities was an effort to preserve as much of this natural biological variability as possible. If the crew were allowed to thoroughly blend genetically, the result would eventually be one homologous genetic ethnicity where most recessive traits were lost. This would leave the crew most critically vulnerable to all kinds of genetic disorders, but it could also potentially leave the crew more vulnerable overall to any potential biohazards on Haven.

In going to a biologically alien world like Haven, it was thought desirable to maximize what limited genetic diversity could be brought with them. The breeding system established on board was a simple one. It stipulated that one could couple with whomever one wished, whether or not from the same ethnicity or gender, but when the time came for a couple to have children, they were required to pick one of their parent’s pure ethnicities for their child. Essentially, people had children to specifically replace themselves on the ship not just numerically, but ethnically and culturally as well. For example, Bao’s mother was a full blooded ethnic East Asian and the granddaughter of the dearly departed Kim In-Su, while her father K’uuna was a full blooded ethnic American.

Although it was in no way a rule or expectation, it had nonetheless become the convention for people to simply choose to replace themselves, thought in some cases they switched the sexes and thus ethnicities of their children; for example if in Bao’s family they had had an East Asian son and an American daughter instead. Since most couples had only two children, the common practice had become for both parents to simply replace themselves in sex as well as ethnicity. Bao was a female East Asian and had been created to replace her mother Sun Jung. They were now on their way to the genetics laboratory to consult with its staff about a replacement for K’uuna, a baby American boy.

As was convention, they would take skin cells from K’uuna and convert them into pluripotent stem cells, from which they would be divided into viable gametes. These would then simply be blended with gametes from an appropriately matched female American crew member either alive or deceased, or from one of the carefully selected and preserved genetic samples brought with them from Earth. After being screened for genetic abnormalities or any other potential problems, the newly formed embryo would then be implanted into Bao’s mother.

There had been talk about how some onboard were opting out of having children of their own and how other couples increasingly would have to step up to supplement their birth rate. Sun Jung and K’uuna had discussed this possibility but concluded that it only bore serious discussion once their second child was born and already growing up. Maybe then they thought, then they might be up for the challenge. Maybe not though, it was hard for them to say at this point, before even having had their second child.

“Have you named him yet?” Bao asked her parents.

“Yes dear, we settled on a name this morning,” her father answered, “his name will be Takoda, in the Sioux language it means ‘friend to everyone.’”

“That’s a pretty name,” Bao declared thoughtfully, then added: “my name means ‘precious treasure,’” she proudly proclaimed.

“Yes,” her mother answered, “and you are,” she added with an extra squeeze of her daughter’s hand. “But don’t forget that it also means ‘protection’ in Vietnamese.” Maintaining one’s genetic profile was somehow insufficient, so a sense of obligation had developed (especially since Earth had gone dark), around preserving an awareness of the cultures from which one originated. As virtuous as such efforts were though, so much was still inevitably lost.

As much as the primary ethnicities were carefully segregated into African, European, West Asian, East Asian, Australasian, and American, so much was nevertheless inevitably lost, both in terms of genetics and culture. For one thing, out of the nine or so original populations of modern humans which evolved in Africa, only one of them was the one which originally left that continent to populate the rest of the planet. This left eight fully unique genetic lines of human beings living in Africa which were now out of necessity, blended into only one monolithic ‘African’ ethnicity. The primary ethnicities were based on an understanding of how humans spread out across the globe once out of Africa.

The first group to leave Africa split and some went north to become the Europeans, while others went east to become the West Asians. Adaptation to the colder, darker climate, as well as some interbreeding with the local Neanderthal population, all led to the lighter features of the Europeans who would one day be referred to somewhat erroneously as Caucasians. The other side of this migration eventually became the Arabs, Persians, and Indians as well as all of their cultural and ethnic derivations. From this West Asian population, a migration further afield took place. This migration was again split as some went east to become the East Asian ancient ancestors to Bao and her mother, while others continued on south-east to populate south-east Asia and Australasia.

The East Asian ethnicity on the ship was a blend of the various Chinese ethnicities, as well as Mongolian, Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese, and a myriad of others. Now they were all one carefully preserved genetic homogeny. The Australasians, emerging from the same migration out of West Asia as the East Asians, populated south-east Asia, the Malay Archipelago and all of Oceania, becoming all of those regions’ indigenous populations. Again, all of the more discrete ethnicities were rolled into the one monolithic group.

Finally, the group now known as the Americans wound up migrating across a transient Bering Strait land bridge, and became isolated from the East Asian population when it re-submerged around twenty thousand years ago. These peoples populated the entire American hemisphere with all of the varied indigenous American cultures and populations. There was a great variety of ethnic groups on the American continent like everywhere else in the populated world, but like every other great ethnicity, they were out of necessity homogenized together as a dam against the complete genetic homogenization of the human species overall.

On the ship at least, as far as the crew of the New Horizon knew, things had been developing much more organically on Earth. There were some rare parts of the world where ethnicity was relatively well preserved, especially in rural areas. Likewise, there were other places on Earth where someone who was a ‘pure-bred’ anything at all was quite the novelty; so generally ethnically varied were the multi-generational inhabitants of most large cities at this point.

There was no element of bigotry or racism involved in these divisions, instead the necessity and importance of maintaining these divisions was well understood and accepted by all. Since mating and procreation were divorced from each other, maintaining these distinctions had no social element to it either, since there was no need to limit or control who became involved with whom. An old vision of ‘different, but equal’ had finally been truly realized, as opposed to simply being used to rationalize discrimination.

They arrived at the genetics lab, and one of Bao’s parents silently ordered the door open. This magic still greatly impressed Bao since she herself still had to operate everything manually. She was not yet quite old enough to have been implanted with her own Brainchip yet. When the family entered, the technician was inspecting one of the opened drawers of biological specimens, carefully checking by eye each spherical containment chamber along the central beam extending into the wall, as the samples were bathed in their ever-present, nurturing blue light. When Bao saw that eerie blue emanating from the apparatus, something clicked in her, and from that time forward it would be obvious to her parents and her beloved teacher Tycho, that she would be one of the most enthusiastic and excitable genetic engineers their little island civilization would ever be graced with.