Launch: Chapter 25

After going to the grave site in the Vancouver borough city of New Westminster, Markus ordered his roadpod to return to Hugh’s place in central Vancouver. Public roadpods were all rentals, and could be found just about anywhere in the city. Once in use a sizable deposit was applied to a user’s account, but was returned once the roadpod was released and only a modest charge was excised based on the distance travelled. The system was so convenient and efficient that between fully subsidized mass transit and these pay roadpods, for most people living in the city there was little justification for having one’s own private vehicle.

Those who did own their own vehicle usually did so for only one of two reasons. Some people required a vehicle with a more extensive range than a battery powered roadpod could provide, and they had modern vehicles which employed small fusion cores. These required refueling only once every few years and thus provided an effectively unlimited range. There were some though, who were enthusiastic collectors of classic automobiles from the twentieth and twenty-first centuries which were run on synthetic biofuels. The effect on the city roads was an interesting juxtaposition; all the vehicles were either generic and drab high technology roadpods, or were by comparison almost cartoonish looking classic cars from two hundred years ago.

The practicality of the public roadpod system was contingent on the fact that the pods were all driverless, and that they were driven exclusively by the onboard computer. The intelligence of the roadpods had a near perfect safety record unlike perpetually error prone human drivers who statistically would have too frequently crashed the pods to make the system economically viable if they drove themselves. The pods driving autonomously could drive in close formation and network together to move around each other with an efficiency and precision well beyond human drivers. Those who still wanted to drive personally needed to be properly licensed, and they were viewed by the intelligence of the pods as a hazard on the road which they needed to be cautious of and allow a wide margin for error around.

Markus’s roadpod arrived onto the city’s downtown central corridor, and made its way down Broadway Street. Vancouver had grown so much that the entire peninsula had become some sort of giant’s pin cushion with one densely packed high rise after another all laid out in a grid. The lower mainland already had a dyke system before the ocean levels began to rise, but like many other coastal cities, they required substantial improvements and extensions. They were fortunate though; many other cities had required far more dramatic measures to preserve them against the rising waters and ever more frequent flooding. Some lower lying areas of the Vancouver lower mainland were filled in with earth trucked in from excavated mountains nearby, material which was also used to build up new and extended dykes, especially around the downtown core. Fortunately the measures required to hold the ocean back here were not as extensive as had been required in a place like Manhattan.

Some of the seemingly endless skyscrapers were office towers and some were residential, but mixed in amongst them there were also towers devoted entirely to agriculture and recreation. Some were exclusively co-op farm towers (known as agri-towers), with floor after floor of hydroponic gardens and protein labs generating fresh produce, grains, meats, and dairies for everyone in the city to eat. In co-op agri-towers, members signed up for tower volunteer hours in return for a discount on the goods the tower provided, in some cases including discounts on the recreational facilities as well. Although some towers were single purpose, many were mixed use and contained an assortment of all with some residential, some commercial, and some agricultural use, all in the same building.

Even some of the agri-towers, though they tended to have agriculture on most of their floors, sometimes had floors dedicated to all kinds of recreational use, from retail businesses and restaurants, to amusement parks, social centres, and public parks. Many of the skyscrapers, both residential and commercial, had a variety of commercial businesses like shops and restaurants at street level too, with a different flavour in every multi block borough. Producing all the animal and plant agriculture locally in these towers allowed all foods to be produced locally, with meaningful positive environmental and social consequences.

A result of this was that most of the farmland in the world was allowed to return to a wild state, resulting in agriculture with a relatively small physical footprint on the environment. It also helped the climate change problem in two ways. For one, it eliminated the pollution resulting from the transportation of foods to and from all corners of the world. More importantly though, using schmeat and schmilk technology meant that live animal farming was largely phased out, which spared the atmosphere the methane emissions of those animals, a gas with a far worse greenhouse effect profile than carbon dioxide.

Aside from the large and historic Stanley Park, there were very few public parks at ground level. The ground between buildings was still used to move people and things between places when not using the underground Skytrain. Instead, in addition to there being some park floors in recreation towers, most buildings but especially those with residential housing within them, had public parks up on the roofs of their buildings. Some included community gardens, but some were simply places to eat al fresco picnic amongst the trees or in some cases even enjoy the swimming pool.

Coming up on his left was one of Markus’ favourite complexes. It consisted of four towers in close formation. Three of them were entirely devoted to agriculture, but the fourth was dedicated to recreation. The agriculture towers were essentially giant green houses with elaborate watering and lighting set ups. Such towers consumed incredible amounts of energy and water, but being such a tightly controlled environment, there was very little waste of these resources so the net consumption of resources was actually much lower than for food produced on traditional farms. Whole series of floors would be devoted to wheat, or to tomato, or to schmeat or various schmilk dairy products. It was the technology of these agriculture towers in major cities around the world that allowed a great deal of the Earth’s agricultural land to be reclaimed by nature and allowed to lie fallow once again.

The recreation tower had just about anything you could imagine such a tower might have, including an amusement park with a roller coaster emerging from the side of the building way up high, which then looped back into it a several floors below. There were whole floor arcades, bars, and at the very top of the tower one of the best rated restaurants in the city. Together these buildings embodied the change that had occurred in urban habitation the world over, that of densification. Vancouver stopped spreading out for hundreds of kilometers around it (though those flatter suburb cities continued to exist), and had instead learned to focus on building up, on densifying into a high-rise mega city like Hong Kong, which had only a few small islands upon which to accommodate millions of people.

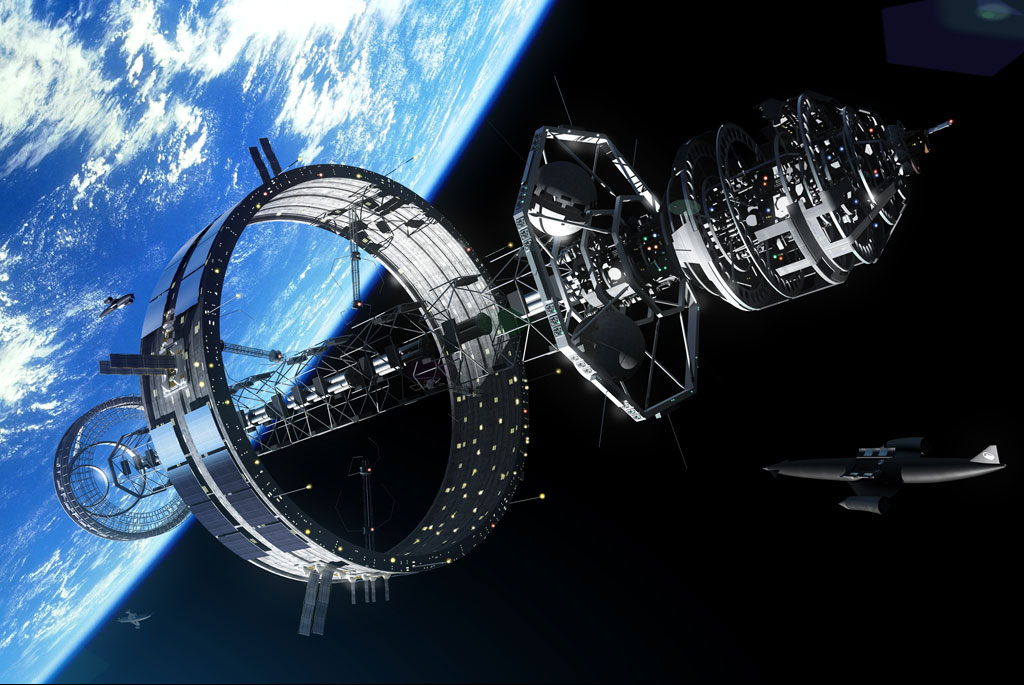

It was something of an oddity in such a large city where millions of people were so physically close to one another, that people could find they were closest to people living hundreds or thousands of kilometers away, while those who lived mere meters away from them were usually total strangers. The perfection of communication technologies made it effortless to maintain close relationships with people whom one was truly close to wherever they were around the planet or in orbit, though it was challenging with people living elsewhere in the Solar System due to the communications time lag.

Instead of forming physically localized social groups, people tended to group together according to the kinds of people they were and the kinds of interests they had. They developed clusters of friendships online with cerebral neighbors instead, though many still made a point of physically getting together with their friends a few times a year when they could. One could have a very active and fulfilling social life while living in a city where one doesn’t socially know a single other person. Devices like the PANEs made this kind of interaction effortless, to the point that one could go to the market with a friend half way around the world, or watch a video on the couch together with several friends in different locations.

Virtual presence and augmented reality had been perfected to the degree that one could look over at the other end of the couch, and if looking through PANEs, see their friend sitting there beside them with no visible indication that it was only their image superimposed onto an empty couch. A more sophisticated version of the same kind of system allowed the use of devices known as avatars which were like simulants but without any brains to speak of. Their speech and movement were remotely translated through the use of special transmitting suits. With two transmitting suits and two avatars, virtual physical encounters between two long distance lovers were even possible.

Near Columbia Street, the roadpod came off of the main road and swung silently into one of the few dozen roadpod alcoves around the base of the tower where Hugh lived. Once docked, its doors swung open onto the building’s main floor lobby.