Launch: Chapter 3

Markus and Hugh stared out the shuttle’s window contemplatively. The sky darkened into a deeper and deeper blue, then purple, and then altogether black and transparent as they cleared the bulk of the atmosphere. To their left they could see the stunning view of Earth from low orbit. Markus had seen the sight many times before, but it somehow always felt as though he were seeing it for the first time; there was something about it which could never be adequately captured in an image.

The shuttle’s main engines reduced their thrust as smoothly and steadily as they had initially come to life, and then finally cut out altogether. All sense of acceleration in any direction completely melted away. Once the engines were fully disengaged, Markus and Hugh were again confronted with the challenge of re-adjusting to the feeling of weightlessness and bumping back and forth in place between their seats and shoulder straps. Markus enjoyed the sensation immensely, but he always found being confined in one’s seat while weightless somehow undignified.

The fuel for their ascent had been provided by a smaller shuttle like craft mounted belly to belly against the passenger shuttle. This obscured and protected the ablative underside of both crafts during the ascent. The tanker shuttle was fully two thirds the size of the primary shuttle, but instead of passengers it carried only fuel and was effectively a highly sophisticated reusable fuel tank.

When mounted together, the two crafts were together shaped like a barrel with one end pulled out into a pointed nose, and mirrored wings extending out from the rear half of the craft. Both crafts had two tail fin control surfaces which created the effect, when both crafts were seen together, of looking like the earliest conceptions of what spacecrafts would look like in the earliest days of rocketry when the only model were Nazi Germany’s V-2 “vengeance weapon,” except shaped somewhat stubbier than that ancient terror weapon, and with large wings which such rockets never had.

With its fuel now spent, the tanker shuttle broke off from the passenger shuttle’s belly, and jetted away before a short engine burn began the process of it falling back down to Earth again. Fully autonomously, it would guide itself back through the atmosphere, slowed by its ablative belly, and guide itself back to the orb-port, where it would be refueled and reattached to a fresh shuttle which would then be mounted under another jet powered altitude launcher.

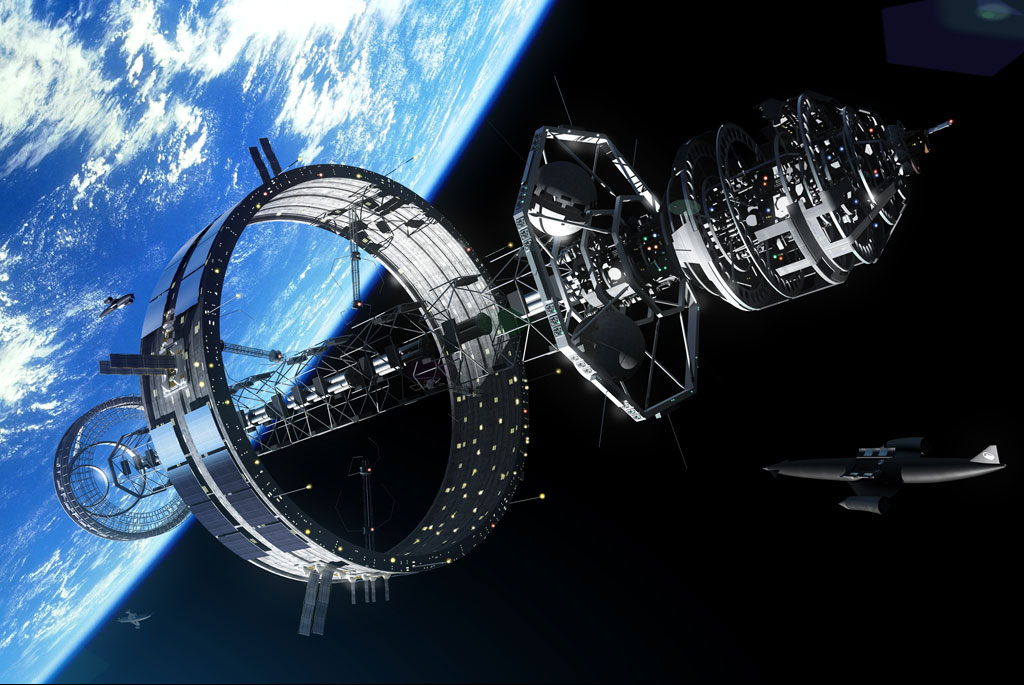

Markus and Hugh were in orbit now, and soft accelerations could be felt this way and that as the auto-pilot adjusted their orbital attitude in preparation for their approach to Orbital One on maneuvering thrusters alone. Craning their necks to look up through the window, Markus and Hugh watched as the gigantic two kilometer wide space station came fully into view as the shuttle rolled over during its approach. The large rotating wheel was in every sense the primary hub of all activity in low Earth orbit.

The station was shaped like a hollow cylinder, and within its twenty floor thick, half kilometer wide walls, people worked, lived, and played. Extending inward from the interior of the cylinder were struts which held it securely to the central hub section of the station. The outer shallow can part of the station rotated to simulate gravity while the inner section counter rotated, which preserved the overall rotational stability of the station, as well as providing a safely stationary docking port.

Markus watched as another shuttle like his detached itself from the central section and drifted away from the station. Once at a safe distance, a few seconds of main engine thrust slowed its orbital velocity enough for it to begin falling back down to the planet. Most of the other docked ships were like the shuttle he’d ascended in, but there were also smaller private crafts as well as larger industrial vessels and long term ships which travelled to the outer Solar System. On the far side of the central section there were a few large ships in the middle of construction, ships which were never meant to enter a planet’s atmosphere, and were thus built in orbit.

Orbital One was also instrumental in planetary and system wide communications. It was the primary radio and laser communications hub for the entire Solar System. Radio light was still the preferred means of communications between a planet or moon’s surface and anything in its orbit, but concentrated laser light had become the standard for communication from one such body to another around the system. It was a far more efficient means of transmitting photons, but one’s aim had to be far more precise than with radio.

Orbital Two and Orbital Three looked very much like Orbital One but were scaled down versions; each was only half a kilometer wide. Orbital One had been build first, as the first part of the three station plan. It had the same dimensions of Two and Three but was much larger. This allowed the construction of a much larger habitat which served a wide array of functions from fueling station to holiday resort destination. Most importantly for the New Horizon mission though, its larger size also allowed it to serve as a platform off of which to build large new ships. Orbitals Two and Three were open to the public as Orbital One was, but they were filled primarily with the orbital offices of transnational corporations, microgravity research laboratories and medical facilities, as well as Peacekeeper operations centres and auxiliary orbital traffic coordinators.

The three stations travelled in the same equatorial orbit and remained equidistant from each other, forming a triangle around the planet. A series of drone stations operating autonomously and on a variety of different orbits networked with the three stations to allow real time keyhole camera, and global positioning systems to every point on the planet. The primary function of the satellite network was to serve as the main communications infrastructure for the whole Solar System. Not only could they together communicate with every point on the planet on demand, but the configuration they used allowed them to also be in direct line of sight for laser communication with anywhere in the system at any time.

The outer section of the station rotated at an appropriate speed to create the perception of gravity towards the interior surfaces on the cylinder, with up being towards the centre of the station and down being out and away from of the station. The interior of this outer cylinder was colloquially referred to as the ‘habitat ring.’ This artificial gravity effect resulted from the centripetal forces arising from the habitat ring’s rotation. Objects like people always want to continue whatever motion they have in a straight line, so when sitting on the interior of a rotating cylinder, their motion wants to carry them in a straight line away from the station at a tangent, but the floor’s surface is perpetually in their way. The effect of this is the floor pushing the inhabitants towards the centre of the station, simulating the effect of gravity pulling down from the axis of rotation.

Orbital Two and Orbital Three had only eight floors in their habitat rings, and each were only 200 meters wide. Being smaller, they had to rotate faster than the larger Orbital One to simulate the same degree of gravity. Their inner decks had a bit less than one standard Earth gee while the outer decks had a bit more, but in general the difference was barely detectable. People are good at comparing things against each other simultaneously but not very good at comparing things presented sequentially, and someone could only ever be one floor at a time.

Where the shipyard was located in the central section of Orbital One, the smaller stations only had space for docking ports and shuttle parking. The docking procedure on all three were the same though. For larger ships, there were four long curved horns which could reach an approaching ship’s airlock without bringing the ship and station dangerously close together. The horns were structurally sound enough to hold the ship in position relative to the station while allowing crew to pass through the hollow interior of the horn. On rare occasions when no large ships were docked, the four horns looked like a long four pronged claw, waiting to strike out and snatch any prey which happened to pass by.

Small craft like the regular passenger orbiter Markus and Hugh were riding in, were by comparison small enough to come right up to the central section of the station after manoeuvering past the horns and any large ships which happened to be docked to them at the time. The orbiter’s airlock was located in its nose, and the craft ever so gradually crept forward towards the complimentary airlock of the station. The two men felt a gentle nudge forward and were held back by their shoulder restraints. They could feel some minor vibrations through their seats and restraints as electric motors winched the shuttle firmly down to the station and pumps began filling the intervening space with atmosphere. Here the craft would remain until it was again boarded by another group of passengers returning to Earth.

A lot of research had gone into figuring out how to keep the human body healthy in a low gravity environment, but the efforts were largely abandoned. It was ultimately realized and accepted that the expense of creating appropriate gravity for people living in space, was just another built in expense of operating in space. Theoretical physicists still claimed that it should eventually be possible to create artificial gravity by other more fanciful means, but they still didn’t know of any way to actually go about it technologically.

The principles were understood, but the technology to put those principles and equations into practice didn’t yet exist, much like the few proposed methods of travelling faster than light. Such things were believed to someday be possible though, and some even mused that the G.S.S. missions were a waste of effort because of it. They speculated that with how long it would take to travel to another star using conventional propulsion, technology would be created in the meantime to get people there far faster, which would allow them to arrive long before the painfully slow G.S.S. missions, even if they left long after the original mission.

Elsewhere in the Solar System, people did live in low gee environments where it was entirely unavoidable. This was generally regarded in the same way as was exposure to ionizing radiation. Both were considered cumulatively hazardous to one’s health, and something which should be avoided whenever possible, but especially for long durations of months or years on end. There were exercise machines which people could use to stem the decay of their bones and muscles, but it was only ever a stop-gap measure. It was just a known law of physiology that it was always easier and safer to move from a higher gravity to a lower gravity, but difficult to adapt in the opposite direction.

Orbital One was much more than just a transportation and communications hub. It was a city in its own right, and the unofficial cultural and political capital of the Solar System in an orbit which varied between three hundred and fifty, and four hundred kilometers above the Earth’s surface. It housed an alternate conference centre which could accommodate the New Commonwealth or United Nations official meetings and ceremonies, but it also housed system renowned restaurants, arboretums and sports facilities. To much controversy relating to the travel expenses involved and the possibility of variable gravity, Orbital One had even hosted the 2116 Summer Olympics to demonstrate the brand new station’s facilities back when Markus was a small boy. Imagination was the only limit to the usefulness of this wondrous station.

Hugh caught sight of the impressive new starship first and pointed it out to Markus. “There she is…”

G.S.S. New Horizon was hard to miss as it came into view; it was one of the largest spaceships ever constructed by humans. Orbital One was the only facility capable of constructing the New Horizon and even so, only certain preliminary stages could be completed while docked with the station. After primary construction was completed and its interior atmosphere was established, the ship was disengaged from Orbital One to initiate its own gravity spin and facilitate construction of the ship’s interior.

The original generational starships were of an entirely different design from this new one. These earlier vessels were each required to accommodate hundreds of thousands of people. Fortunately, the religious authorities commissioning the projects commanded massive economic resources, and their more brute force approach was to capture an asteroid several kilometers across, and gently bring it into a high Earth orbit. They then set construction drones to work hollowing out the interior, harvesting liquid oxygen and hydrogen from the water they found in it, sorting out the other raw materials they would need on their journey, and jettisoning the rest into an ever growing waste bag.

Steadily and surprisingly quickly, the tireless drones successfully hollowed out the asteroids while leaving a sufficiently thick outer wall to shield the interior from dangerous cosmic rays, a perpetual silent hazard in space. Their task complete, those drones then returned to dock in their control satellite and patiently waited to be commissioned for some other project. At this point a different set of construction drones designed to work alongside humans all detached from a different construction satellite and approached the work site. These drone teams set to work building an exterior docking port out of the hole the first drones had originally dug through and travelled in and out of while hollowing out the interior of the asteroid. After constructing the docking port, establishing a stable atmosphere inside the asteroid, and giving it a gravity spin, the drones and human crews began constructing the interior living spaces of the ship.

Later on the asteroid ships were each supplied with a bank of twelve of the most powerful fusion cores commercially available. Six of the cores were dedicated to keeping the humans alive onboard, while the other six each independently powered their own ion engines. While the New Horizon used advanced prototypes for their power core and ion engines, these earlier missions merely used the most powerful mass produced systems available at the time.

The high capacity ion drives were essentially just bolted onto the side of the outfitted asteroid, and a single liquid rocket engine was installed at the rear of the ship in order to use up all of the volatile fuels harvested from the asteroid during construction. This allowed them to start their interstellar journey more directly than the New Horizon could. Without a liquid rocket booster, the new G.S.S. would instead need to use its weaker ion engines to expand its orbit around the Earth wider and wider. It would then boost its orbit away from the sun on an escape vector out of the Solar System while maintaining their orbital velocities and getting a gravity assist speed boost from Jupiter, Uranus, and Neptune. The earlier G.S.S. vessels could instead just point in the direction of their target star, and light both their liquid rocket engine and their ion drives, then continue on under ion power once all of their volatiles were used up. This allowed them to get a jump start on their great lumbering out to the stars.

The New Horizon was an entirely different animal though. Small and purpose-built, every component was precisely engineered. Instead of hundreds of thousands, it was only built to accommodate a hundred people at launch, and up to three hundred by the time of their arrival. It was built from scratch using advanced prototype technologies instead of off the shelf components.

The blueprints of Orbital Two and Three were the original basis for the New Horizon’s design. It was about the same size as the smaller stations, but with obvious and significant differences. Although the exterior of the outer ring was matt grey just like the exterior of the space stations, there was one particular section which caught Markus’ eye. It was a strip of the inner surface of the rotating habitat ring which glimmered with reflected sunlight. He didn’t know what was causing the effect, but at the right angle of reflection that glimmering could be positively blinding as it reflected the full might of the sun.

Instead of a docking port in the middle like the stations had, there was instead a stubby cylindrical module which housed the large prototype fusion power core, which Markus’ family’s company had designed and constructed specifically for the mission. Extending from there were four long cylindrical casings arranged around an obscured central access tube. Most of these long and narrow cylinders were taken up by the cold storage tanks which held either deuterium fuel for the fusion reactor or the liquid xenon fuel which powered the ion engines. Although the hydrogen isotope deuterium was easily harvested from ‘heavy water’ on Earth or from asteroids and meteors in space, the liquid xenon fuel was a commodity only made widely available after widespread use of ion engines made it economically feasible to begin harvesting it from Jupiter’s atmosphere. Beyond the storage tanks and situated at the far tips of the long tubes were the currently powered down yet extraordinarily powerful prototype ion drives.